“Bodie ghost town” by PDPhoto.org. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons.

People who enjoy ghost towns have been known to visit one of California’s most famous examples: Bodie, in Mono County.

High above the treeline and subject to brutal eastern Sierra Nevada winters, Bodie is a well-preserved gem of a town. The site of a gold strike before fires decimated much of it, a small portion of Bodie still stands today. Its interiors are covered in dust and memories and, they claim, left just as they were when the state deemed it a state park in 1962. In fact, California coined a new term to describe its upkeep of the town: “arrested decay.”

It’s so famous, some may say it’s California’s official gold rush ghost town.

Well, those people would be right.

Seriously. It’s in the Government Code.

It didn’t get there without some controversy, however.

Section 429.7 falls in Division 2, Chapter 2 of the “General” title of the Government Code, under “State Flag and Emblems.” California has a state flag, of course (Gov. Code § 420), but it also has a state fossil, a state tall ship, and a state soil (the saber-toothed cat, “The Californian” and San Joaquin Soil, respectively). California first started declaring state emblems and flags in 1911, with the designation of the official flag, and it has been designating new things ever since.

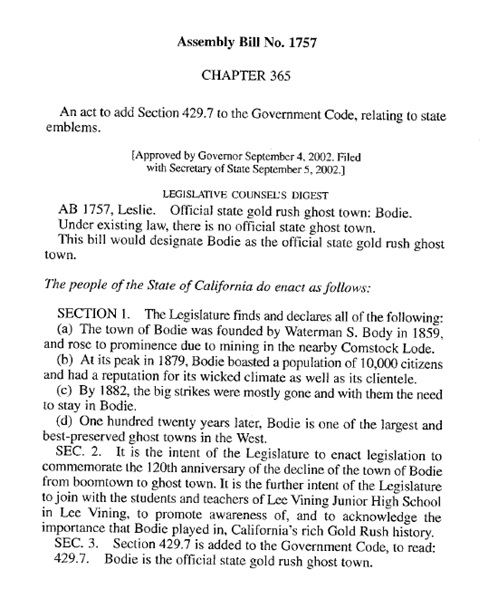

The Legislature added Bodie in 2002.

But why?

The kids.

Assembly Bill 1757 was carried by Assembly member Tim Leslie of the Fourth District, who indicated the students and teachers of Lee Vining Junior High School in Mono County were the force behind this bill. It was the result of the Assembly member’s “Write a Bill” challenge, designed to encourage junior high students to participate in the legislative process.

Further reasons for the bill included the fact that the designation would commemorate the 120th anniversary of the town’s decline, and it would “promote public awareness and to acknowledge the importance that the town of Bodie played in California’s rich Gold Rush history.”

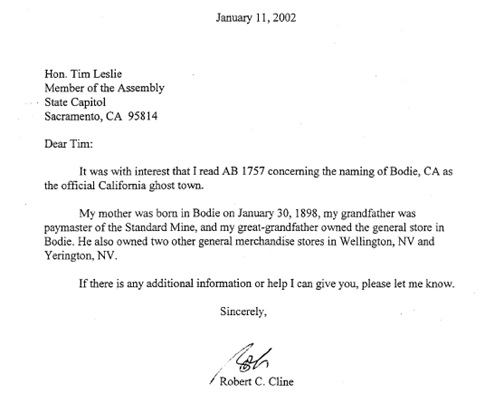

Others supported the bill, including descendants of owners of Bodie’s DeChambeau Hotel and some who grew up in the area. One letter writer had extensive ties to the area – his mother was born in Bodie, his grandfather was paymaster of the Standard Mine, and his great-grandfather owned the town’s general store.

There were a few questions, though. The biggest came from a tourism competitor. Calico, in the Mojave Desert in San Bernardino County, is another popular California ghost town. Its supporters were concerned that by deeming Bodie the state’s official ghost town, Calico would have a “competitive disadvantage when competing for state and federal grants.”

As introduced on January 7, 2002, section 429.7 would have read, “Bodie is the official state ghost town.” In a May 2, 2002 letter to the Legislature, San Bernardino County expressed its concerns about Bodie being “the” state’s official ghost town. The county requested the section be amended to change “the” to “an.”

On May 13, the bill passed the Assembly and went to the Senate, where thanks to pressure from San Bernardino County, the bill failed in the Senate and was moved to the inactive file.

A few months later, on August 13, the Legislature moved the bill from the inactive file and amended it to add “gold rush” before “ghost town.” As Senate Floor Amendments Committee Analysis stated, the purpose of this change was “[t]o remove concerns expressed by the County ofSan Bernardino – home to ‘Calico Ghost Town’ which was noted as a ‘silver’ mining town of the early West – and to make the distinction that Bodie was a ‘gold’ mining town.”

Three years later, Calico was deemed the state’s “official silver rush ghost town.” (Cal. Gov. Code § 429.8) Today, both towns continue their lives side-by-side in the Government Code.