Anybody weaned on shows the likes of “ER” is familiar with Hollywood’s version of a hospital emergency room: A place where, at regular intervals, a cadre of professionals, along with a patient on a gurney, slams through a pair of swinging doors and rushes inside, all while paramedics shout rapid-fire bits of information to hospital staff.

Medical professionals can tell us how, or even whether, the above scene squares with reality. We do know that in real life, if you have a medical emergency and 911 responds, you likely will first receive advanced medical care on the scene – long before you reach a hospital – from a paramedic or EMT.

It’s automatic. Expected.

And, as it turns out, it’s a relatively new concept.

In California, the field originated with the stroke of the governor’s pen.

Before the late 60s, outside of a military context, the quality of ambulance services in the United States varied wildly. (The military had long experience with trained medics.) Back then, ambulances were staffed by attendants of varying degrees of training and equipment – some cities had highly trained, full-time staffs, along with a dispatching unit that ensured fast arrival to a hospital, while others employed “unschooled apprentices lacking training even in elementary first aid.” In half of U.S. cities, ambulance services were provided by mortuaries, who had the only vehicles capable of carrying a prone patient. Most lacked vehicles big enough to allow care en route to a hospital.*

In 1966, the National Academy of Sciences, National Research Council published the results from its three-year study on accidental deaths in the United States. Titled “Accidental Death and Disability: The Neglected Disease of Modern Society,” this paper noted that other countries had lowered their accident mortality rates by staffing ambulances with physicians and providing care on the scene and en route to the hospital.

The study noted another striking find: Statistically, soldiers in a warzone were faring better than the American civilian public regarding emergency care.**

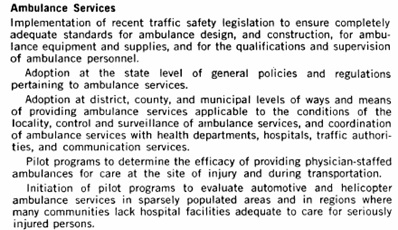

The paper made the following recommendations regarding ambulance services:***

Around this time, Los Angeles was conducting its own study into a more narrow area of emergency medicine: Heart attacks. While U.S. hospitals had managed to reduce its mortality rates for heart attack patients by instituting coronary care units, two thirds of coronary deaths were still occurring before the patient even reached the hospital.

In 1969 the Los Angeles County Heart Association sponsored a Coronary Ambulance. This ambulance was equipped the same as a hospital coronary unit, and it serviced the Inglewood-Centinela area. It was a pilot program and a cooperative between the Heart Association, the county, and several area hospitals.

To comply with state law at the time, these ambulances needed to be staffed by a nurse or physician. However, there weren’t enough nurses and physicians to keep up with the demand for the ambulances.

In stepped the California Legislature.

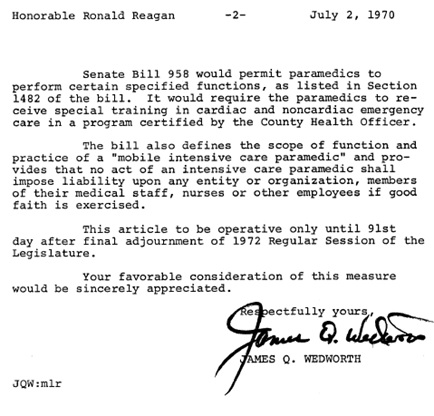

On April 1, 1970, Senator James Wedworth introduced Senate Bill 958. This bill proposed adding provisions to the Health and Safety Code regarding paramedics, specifically authorizing designated hospitals “to conduct pilot program relating to mobile intensive care paramedics.”

In June 1970, Assembly member Larry Townsend became a co-author, and the measure was named the “Wedworth-Townsend Paramedic Act.”

The county and the city of Los Angeles both wrote Governor Reagan, urging him to sign the bill. Senator Wedworth also wrote Governor Reagan, asked for his signature, and described the bill:

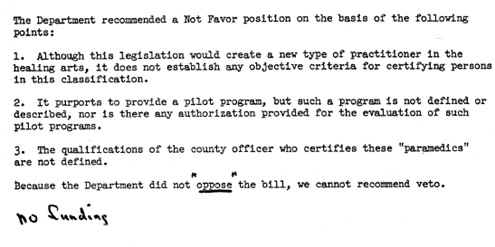

The Department of Public Health had concerns with this bill, however. In an enrolled bill report dated July 9, 1970, the Department stated the following:

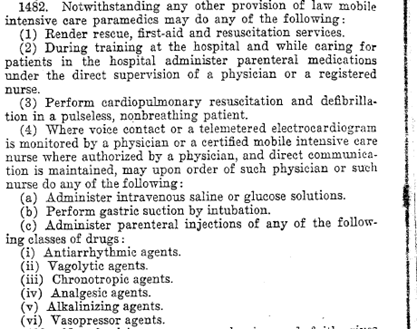

Governor Reagan signed the bill on July 14, 1970. It was a very short bill – only three pages. Former Health and Safety Code Section 1482 outlined exactly what functions mobile intensive care paramedics, as they were called at the time, were allowed to perform:

It was an urgency statute – which means it went into effect immediately upon the governor’s signature – and it by its own terms it expired after the adjournment of the 1972 regular session. However, the act was extended and it was amended several more times through the seventies.

In 1980, the Legislature replaced it with today’s Division 2.5 of the Health and Safety Code, “Emergency Medical Services.”

The Wedworth-Townsend Act was repealed by its own terms, effective January 1, 1982.

________________________________________________________________________

*”Accidental Death and Disability: The Neglected Disease of Modern Society,” Division of Medical Sciences, National Academy of Sciences, National Research Council, pp. 12-13 (1966)

**Id. at page 12

*** Id. at page 35

Photo credit: “Nine One On Phone Shows Call Emergency Help Rescue 911,” by Stuart Miles. Via freedigitalphotos.net